Berlinale 73: The assault of the present on the rest of time

“… it is precisely the faculty to evoke the future, near or remote, that determines how interesting life is.”

—Marc Augé, The Future1

The 73rd edition of the Berlinale had begun inauspiciously. Budget cuts had put paid to the official parties, many feted productions had once again sat out the competition for Cannes, adolescent climate activists declaring themselves the “Letze Generation” were superglued to the red carpet outside the Palast in protest at the festival’s choice of corporate sponsor (Uber), meanwhile “a bad actor, a professional comedian, under the eye of other professionals in their own professions” (to take the words of the late Jean-Luc Godard) was once again beaming in to an audience of celebrities to demand military supplies, the weather had taken a turn from the inclement to the truly misanthropic, and now at their inaugural press conference the International Jury President Kristen Stewart was fielding multiple questions from eager male journalists on her suitability for the role: “Some European films you’ve enjoyed in the last few years?,” “What’s your familiarity with Japanese cinema?,” “What do you think makes a good film?” [“Why exactly are you here again, Bella Swan?,”]. Instead of procuring her LetterboxD handle or reminding the inquisitors of her inestimable arthouse credentials, Kristin cast her eyes down, exhaled, and glowered from somewhere deep within her chunky Chanel tweed suit. Then, after a pregnant pause, she erupted into an exaltation of the power of art as a form of quirked-up ekstasis:

It’s the job of an artist to take a disgusting and ugly thing and sort of transmute and put it through your body and pump out something more beautiful or more helpful, something considered and not something knee-jerk reactive, I think we’re living in the most reactive, emotionally whiplashed time. To sit and have a moment to actually digress, and look and see what people have pumped out of their own bodies in response to the world that’s falling apart around us? That was an opportunity that I obviously couldn’t refuse.

Fig. 4: The International Jury 2023: (f.l.t.r.) Radu Jude, Valeska Grisebach, Carla Simón, Francine Maisler, Kristen Stewart, Johnnie To, Golshifteh Farahani © Dirk Michael Deckbar / Berlinale 2023

As always, the fragile future of film itself was also rolled out for inspection. Why were we all here? Shouldn’t we have been doing something more morally significant with our time? There followed a round of shallow and unconvincing homilies to arthouse, small-budget, and independent cinema’s capacity to mediate the wider social cataclysm beyond the festival’s air-conditioned multiplexes (principally the earthquakes in Turkey/Syria, the Iranian Women’s Revolution, and the one-year anniversary of the escalation of the war on Ukraine), as well as some entreaties to how we should all don kid gloves and soften our critical faculties because of quite how hard it is to get a film made these days. It fell to the Chinese martial arts film director and producer Johnnie To to inject some sobriety into the proceedings, as he declared via his Cantonese translator that “Films now I feel . . . have gotten worse. Films across the globe have gotten worse. It is like my own world of watching films is disappearing little by little. I hope this is just for a short time, and that films will get better in the future.” Fellow jury member Radu Jude (recipient of the Golden Bear here some years back for his neo-Godardian Bad Luck Banging, or Loony Porn) was sympatico but less nostalgic, opting instead for a quote from the experimental filmmaker and writer Isidore Isou’s phenomenal Traité de Bave et d’Eternité (1951) that: “cinema is the industry of money and stupidity.”

Indeed there was no shortage of either on display at the Canadian Embassy’s party on Saturday night, one of countless receptions where the air was thick with boasts of closing SVOD (streaming video on demand) and international distribution deals and the Riesling seemed in no danger of running dry. The denizens of the European film industry gaily filed in to the embassy under the hallow gaze of Justin Trudeau’s framed portrait to celebrate the revivification of the post-pandemic EFM (European Film Market) at Gropius Bau, where as a press release breathlessly reported, there had been: “record results with 230 stands and 612 companies from 78 countries and a total of over 11,500 market participants from 132 countries . . . 773 films were shown in 1,533 screenings, including 647 online screenings and 599 market premieres. The total number of buyers also rose to 1,302. 629 film projects presented on the new Producers & Project Pages.”

So much then for the disgusting and ugly thing of which Kristin, Johnnie, and Radu had all spoken—so much for the money and stupidity, the mediocrity and the emotional whiplash—but what was there to be seen of their transmutation into something more beautiful? Something more helpful? Something considered?

Fig. 5: Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you by Walid Raad USA 2022, Forum Expanded © Walid Raad. Courtesy Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg, photo: Steven Probert

Fig. 6: Group photo of G7 members under the Alps at the Schloss Elmau Summit, 2022

Expanded Forums

In his Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste Bourdieu reminds us of the accepted protocols of aesthetic discernment that govern the “aristocracy of culture.” In the world of the Berlinale, this politics of taste works as follows: the mandarin deplores the star-gazing parvenu who hews doggedly to the Panorama and official Competition programming, preferring instead “to sacrifice contemplation of the work to discussion of the work, aesthesis to askesis.”2 For such attendees “I’ll probably just stick this year to the Forum, Forum Expanded, and Encounters” becomes their mantra. Here, they surmise, apparently independently of one another but wholly in accordance with their wider social habitus, is where the future of film will be found at this festival—if it is to be found anywhere.

As in previous years, the direction in which the Forum gazed this year was by and large retrospective, archival, intent on excavating moments of futurity from the wreckage of personal and political histories and their erasures. The form correspondingly taken by so much of the film or moving image work on offer was, intently or otherwise, correspondingly retro, with light-leaking 16mm still the preferred weapon of choice (even when, as in Eduardo Williams’ A Very Long Gif, acknowledgement was made to the existence of digital media). The origins of the “expanded cinema” movement that gave this strand its title were acknowledged through the beautifully presented installation of Takahiro Iimura’s Time Tunnel (produced for Kino Arsenal back in 1973), while Tenzin Phuntsog’s mute, split-screen family portraits and Tamer El Said’s Borrowing from a Family Album tried to cleave open a communal space from within the living archive of the family.

The most memorable of all the installations on display at Silent Green, Walid Raad’s Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you took up the entire rear wall of the main hall in the Betonhalle. Here two one-minute video loops of enormous waterfalls oscillated in the gloom against the concrete-like silk curtains. Assembled at the foot of these waterfalls were a collection of cardboard cut-outs that on closer inspection revealed themselves to represent different world leaders (Bill Clinton, Deng Xiaoping, Reagan, Thatcher, and others), both groups dwarfed by the torrential enormity of the sublime flow behind them—recalling those pictures of world leaders at the 2022 G7 summit dwarfed against the Bavarian Alps. In his show notes, Raad clarifies the piece in typically tongue-in-cheek fashion:

During the Lebanese wars, many militias formed, almost out of the blue. They were supported with cash and weapons by different patrons. To honor their backers, many militias decided to name beautiful Lebanese waterfalls after the leaders of the countries backing them. And when the alliances shifted, they simply decided to rename the waterfall again, and again, and again. Locals today refer to all waterfalls as the “Fickle Falls.” Here, I am exhibiting an installation inspired by this story. Below the falls, I placed all the leaders who had the waterfalls named after them.3

The enfeebling, ironic gesture of Raad’s work—which reduced these world leaders to inert 2D tourist props assembled on a flat plane against the backdrop of a gargantuan flow they could neither significantly control nor influence but could only symbolically inscribe themselves onto—managed to visually render the paralysis of genuine future-thinking in the moment of our so-called “polycrisis” more successfully than most other works here on display.

Fig. 7: ALLENSWORTH by James Benning USA 2022, Forum © Courtesy of the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Domestic Terrors & Quotidian Horrors

Unlike the more “rapid-response” artforms (poetry, theatre, painting), cinema is more bovine. For boring procedural reasons it tends to move slowly, to chew over the rough cud of the contemporary for longer before regurgitating it. There was, then, predictably enough no explicit pandemic film in this year’s competition. Perhaps there won’t be for another decade, which might not be any great loss. However, we are now at a sufficient distance from the first wave of the COVID pandemic in the production cycle to perceive its clear imprint on many of the other films presented here at the festival. Most notably that “assault of the present on the rest of time”—the experience of life under lockdown. The most tangible influence of those long, brooding months spent indoors, in which the world both massively expanded (in terms of our heightened consciousness of global interconnectivity) and contracted (at the level of the day-to-day), seems to have been (as some predicted at the time) a return to the “sealed drama” or “chamber piece” genre. Shot largely in one location and exploiting both interpersonal dynamics and the quotidian horror of the home for dramatic effect, rather than montage or exotic locations, such films (think: Hitchcock’s Rope, Polanski’s Repulsion, Haneke’s Funny Games and its cognates [Lanthimos’s Dogtooth], the cardinal films of the zombie genre such as George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, or meditative studies of domestic claustrophobia such as Ackerman’s recently garlanded Jeanne Dielman, Duras’s India Song or Jean-Daniel Pollet’s Dieu sait quoi) transform the home from the promised site of respite, sanctuary, and calm (a state achieved on film often only through contradistinction with the frenzy of the world beyond it), into something far more sinister. The home, or the property relations undergirding domesticity as such, emerges from such dramas instead as a state of semi-voluntary confinement and stultifying routine, an incubator of petty paranoia and suspicion, an enervating island where violent fantasies can develop.

Fig. 8: Sydney Sweeney in REALITY by Tina Satter USA 2023, Panorama © Seaview

This reconfiguration of the domestic was most evident in Tina Satter’s Reality, a taut thriller about the ordeal suffered by the NSA whistle-blower Reality Winner. Doorstopped by two FBI agents on her day off for having mishandled sensitive information at her workplace, the conceit (which only occasionally veers off-piste into gimmickry) that gives the film’s title its ingenuity and the film itself its power is that the entire script comes verbatim from the recorded transcript of Winner’s actual interrogation. It’s all real, folks! Though in part further evidence for what David Shields christened “reality hunger” over a decade ago—as part of diagnosing the increasing tendency of American art to hew ever closer to documentary, in answering a wider public fear or suspicion of the wholly fictional and insatiable appetite for true stories4—Reality is nevertheless thoroughly Bovarian in its attentiveness to the utterly quotidian. The translations Winner performs for the NSA from Pashtu and Dari are done on pretty, scented paper, the FBI agents in their ghastly beige slacks that interrogate her in her house express an all-too-genuine interest in her dog and precisely how much she can powerlift, and the set design of the house itself (which temporarily becomes a prison) is wonderfully uncinematic (she has a Pikachu bedspread). Much as Flaubert famously declared “Madame Bovary, c’est moi!” the audience could also be tempted to exclaim such of Reality Winner—here memorably portrayed by Sydney Sweeney, graduating from prestige television to film proper—as she initially exchanges niceties with the agents, and welcomes in the SWAT team that turns her modest suburban home upside down and searches beneath her Pikachu bedspread. Her calm, ex-military manner leaves ample room for speculation on her true motives to percolate within the extraordinary ordinariness of the encounter, while the use of Winner’s real transcript preserves the repetitiousness, the inarticulacy, and the circadian rhythm of actual speech. She can’t leave, and yet these men, her wardens, are also her guests.

Fig. 9: Willem Dafoe in INSIDE by Vasilis Katsoupis GRC, DEU, BEL 2023, Panorama © Heretic

Another biting subversion of the domestic came from Vasilis Katsoupis’s debut feature Inside. Here, once again the home becomes carceral—as a wiry and impish Willem Dafoe plays an art thief confined (locked down?) to a luxury penthouse he has been assigned to heist an Egon Schiele from, incarcerated by the whims of the penthouse’s malfunctioning “Smart Home” security system. Marooned in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, living at the mercy of the demiurgic security system’s stochastic fluctuations in temperature and his diminishing mental and physical resources, he has to become resourceful—“hacking” the meagre provisions of this affluent home-as-asset (understocked cupboards, no running water, and a near empty “smart” fridge that plays the Macarena upon opening). In this manner Inside deftly ironizes the survivalist narratives of films such as Peter Brook’s Lord of the Flies, Castaway, or (more recently) the final act of Triangle of Sadness, as a folly of supreme resourcefulness in an environment where it is usually never required. The stochastic terror of the “smart” security system that controls his world, a sort of terrestrial and mute version of Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey, also adroitly channels contemporary fears of algorithmic governance.

Like Des Esseintes in J. K. Huysman’s À Rebours or Basil in Wilde’s Dorian Gray, Dafoe’s art thief is suffocated by the empty foibles of this apartment and its conspicuous luxury art—the Maurizio Cattelan print on the wall, the Tracy Emin neon that short circuits when the sprinklers are randomly detonated and the penthouse floods, the Stan Douglas film on a loop in the dedicated screening room to which he learns the words verbatim. Indeed he only acquires an agency that goes beyond the short-termist and reactive by adding a piece of his own to the collection. Endeavouring to escape, or transcend, his situation through the skylight in the ceiling, he becomes a supreme bricoleur—fashioning a sort of Tatlin Monument from an assortment of Scandinavian furniture and coffee table art monographs to help him climb up to freedom. This postmodern gothic thereby provides, however obliquely, the best COVID film yet.

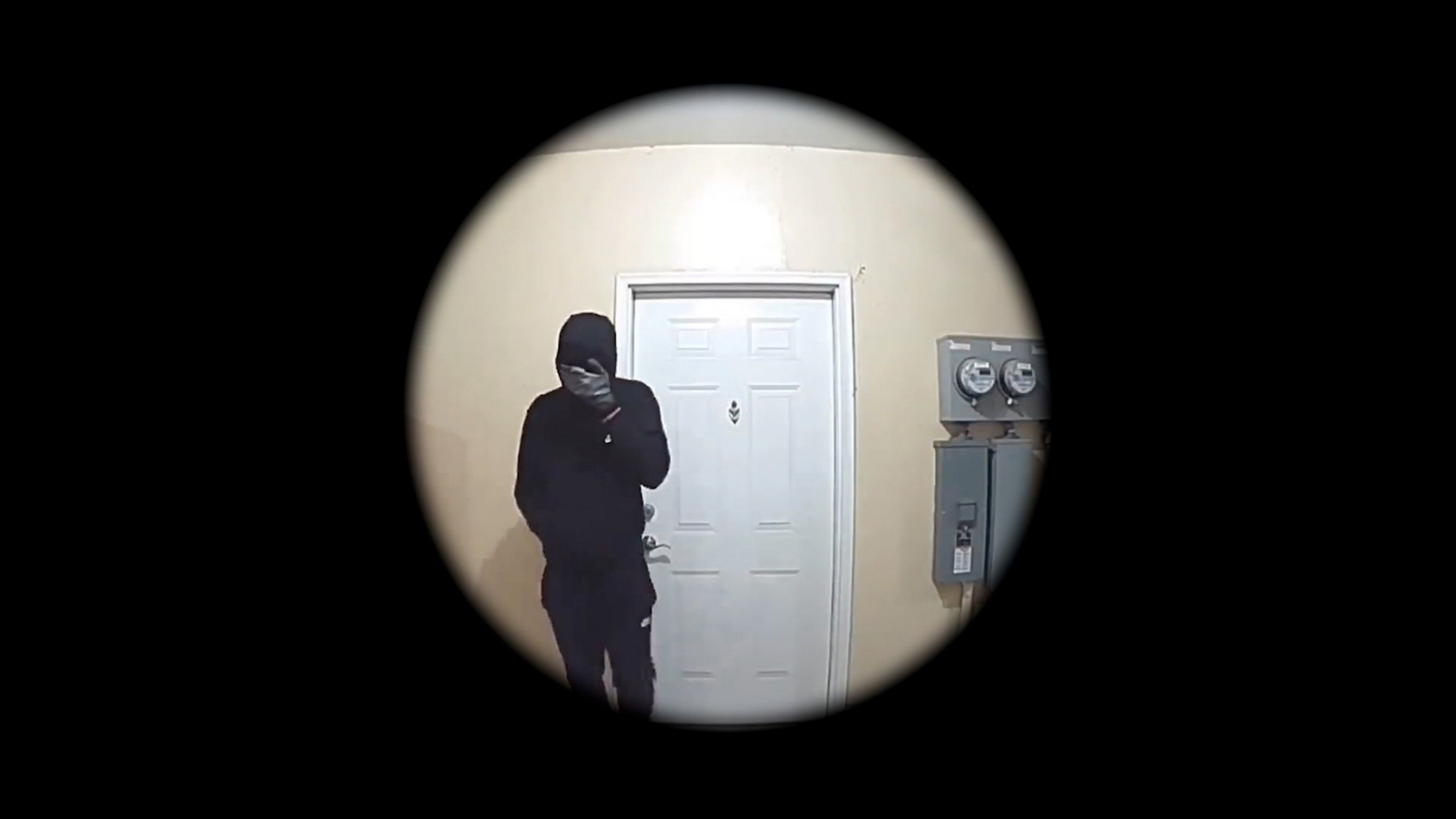

This co-imbrication of the technological, the carceral, and the cinematic—the sense that we are increasingly technologically monitored in and monitoring the spaces that were once the preserve of the bourgeois ideal of privacy—was also explored in Graeme Arnfield’s outstanding found footage film Home Invasion. Comprised entirely of the ellipsoid footage auto-recorded by the “Ring Alarm” home security system, which works by motion capturing anything on its doorstep, allowing curtain-twitching homeowners to forward “anything suspicious” directly to local law enforcement, Arnfield provides a revelatory genealogy of the doorbell as an index of suburban alienation. Spying through this ellipse we observe an approaching home invader in a balaclava, an overburdened DHL delivery person, a sky made brilliant fuchsia by a forest fire, a variety of animals that have strayed from the woods into suburbia. In this way, Home Invasion works within the terrain of what Harun Farocki, and subsequently Jussi Parikka, have theorized as “operational images”:

Operational images are, in Farocki’s words, ‘pictures that are part of an operation,’ implying the primacy of action and function instead of a picture to be seen and interpreted for meaning. Perception is tightly coupled with action, immediate or delayed. This coupling systematically operationalizes terrains and targets. Hence guidance systems, movement, tracking, measurement, and precision are some of the contexts that take precedence in such images that are often, in terms of visual history, ‘inconsequential,’ as Farocki bluntly puts it.5

Fig. 12: ALLENSWORTH by James Benning USA 2022, Forum © Courtesy of the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Fig. 13: Diagram from Paul Schrader’s “Rethinking Transcendental Style,” in Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, (Berkley: University of North California Press, 2018)

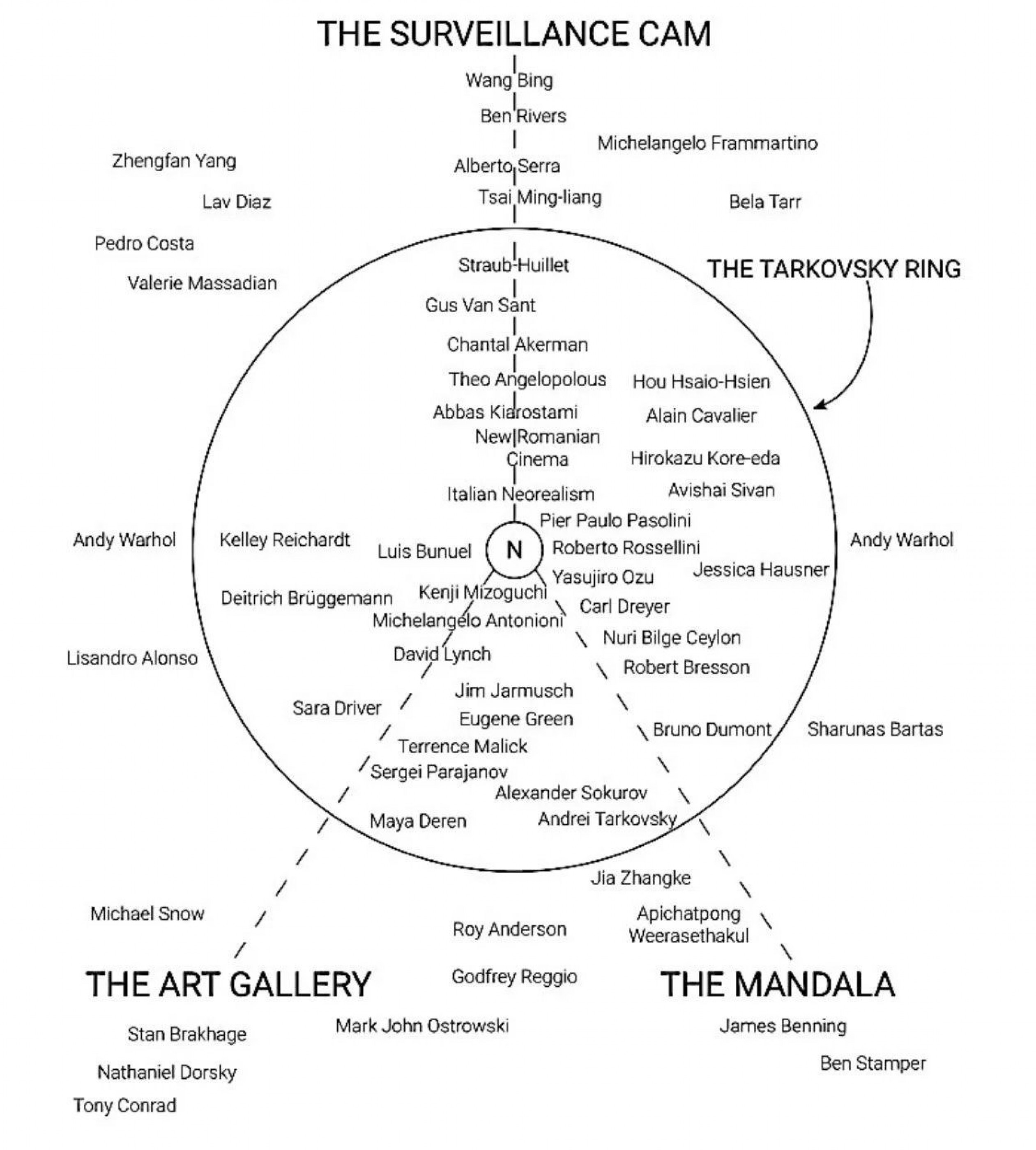

In his examination of the so-called “slow cinema” movement, as part of an introduction to the reissue of his epochal Transcendental Style in the Cinema, Paul Schrader tabulated three loose vectors of activity intersecting the so-called “Tarkovsky Ring” in contemporary cinema: The Art Gallery, the Mandala—and the Surveillance Camera.6 Though he situated the 80-year-old West Coast structuralist filmmaker James Benning along the “mandala” vector, there is undoubtedly something surveillant about Benning’s now well-established late style of immaculately composed landscape shots of equal duration. Like the operational images of CCTV, his camera never moves from its tripod nor seeks to overdetermine or cast judgement upon what it presents to us. Unlike such images however, Benning’s remain undecidable—even to the filmmaker himself. The film he presented at this year’s festival, Allensworth, was no exception. As in his United States of America (2021) or Four Corners (1998), Allensworth deals, obliquely but powerfully, with the myriad lost futures of the American Dream.

Introducing his film to a packed-out audience at the Delphi Filmpalast (several of whom evidently didn’t understand quite what they were in store for, leaving in fits of giggles during the second five-minute take) Benning declared it a “mystery, of sorts”—twelve shots corresponding to the twelve months of equal duration in a near-deserted community of jerry-built shacks, past-their-best civic buildings, and scrubland. As he later explained, what we were looking at was the first town in California to have been established, financed, run, and inhabited solely by African Americans.7 What we were looking at, lingering over and within, however, was not the original settlements themselves but replicas of the buildings from 1908–18, subsequently reconstructed and repaired in the 1970s after decades of purposeful neglect and meddling by white state governors that led to the mass depopulation of the settlement. Within an imageworld where frenzied variation is so often (mis)taken as the imprimatur of contemporaneity,8 the curious power of Benning’s lost futures remains (as Jonathan Rosenbaum observed some two decades ago) their capacity to produce “moments when standing still is as important as moving, when thinking is as important as feeling.”9

Fig. 14: (l-r) Thomas Schubert, Paula Beer, Langston Uibel, & Enno Trebs in ROTER HIMMEL | AFIRE by Christian Petzold DEU 2023, Competition © Christian Schulz / Schramm Film

Red Sky at Night (“Work won't allow it”)

Christian Petzold’s Roter Himmel (curiously translated for English distribution as Afire) provided one of the most enduring cinematic experiences of the Berlinale. Here, finally, after the uncountable prestige films and standard festival fare in the competition, one found something genuinely “pumped out of someone’s body in response to the world that is falling apart around us,” something which was neither didactic nor morally foreclosed in its depiction of human foibles and narcissism. Something that formally bound together the cosmological and quotidian registers of social life—meteorology and desire—into a queasy, tonally uncertain gestalt.

Indeed, as the director later clarified at the press conference, the germ for this film lay in his own COVID fever dreams in 2020, where, as he convalesced, he read of the forest fires then raging in Turkey. Later, upon visiting the scenes of devastation there with his wife, he was struck by the Totenstille, or silence of death, in these forests.

The second film in what is set to comprise an “elemental quartet” loosely bringing together folkloric concerns with earth, wind, water, and fire after 2020’s metaphysically overseasoned Undine, Roter Himmel was on its surface (rarely where the interest in anything other than planets or pizzas is to be found) a deceptively simple thing. Twenty-something writer Leon (made somehow ageless by the actor Thomas Schubert’s puppyfat face) joins his friend Felix on a summer vacation to the latter’s family Sommerhaus on the Ostsee, purportedly to finish up work on his second novel. It transpires that Felix’s mother’s friend Nadja (Paula Beer) is also staying there, with nocturnal visitations from her lover, the lifeguard David—their presence only presented to the viewer for the first third of the film metonymically, through the cries of passion that keep the boys awake at night, the crumpled ben linen, and the lasagna she leaves out for them in the morning. Here, along the windswept dunes of Rostock, a German vernacularization of the French “summer film” begins to play itself out; Porcine à la plage. Priggish, stiff, incapable of true relaxation, wonderfully imperceptible to the emotional reality of others (his favourite expression is “I can’t. Work won't allow it.”), and preoccupied by his own sense of intellectual superiority over his friends, Leon is superbly unlikeable. In this characterization, and his stubborn refusal to enter into the Faustian bargain that Hollywood terms the “hero’s growth”, Roter Himmel—unlike the one-note prestige film biopic of Ingeborg Bachmann also presented in competition from Margarethe von Trotta, which follows the established path dependency for every generic film about an extraordinary writer—is not least that rarest of things: a truthful Künstlerroman.

Perhaps more interestingly, however, is how Roter Himmel mediates the encroaching ecological apocalypse (here presented in the form of the rampant forest fires that Leon breezily dismisses, alongside everything else). The film behaves as a sort of centrifugal partner to Pasolini’s Teorema. Whereas, in this film, Terrence Stamp—playing the charismatic crypto-messianic stranger who arrives in a bourgeois Milanese household, seduces all its members, only to then leave at short notice—centripetally attracts the energy of all the other characters in the film, Leon somehow manages to repel at every turn. When he entrusts Nadja to read the draft of his sophomoric second novel (entitled Club Sandwich), she devours the entire thing only to return it to him, with a brusque “no”; when his publisher arrives to also read this doggerel, he instead becomes seduced by the charm of Felix’s UdK diploma project and Nadja’s doctoral research; and when it comes time for his grand declaration of love for Nadja, circumstances he has been disavowing all along intervene to distract her. As in Teorema, where Terrence Stamp’s antics in the Milanese loggia are intercut with scenes of a desolate desert landscape, in which the patriarch of the household memorably sojourns to scream, here we likewise feel the steady encroachment of the “disaster to come”10 in the form of the raging forest fires that give the English film its title.11 Unlike in the histrionics of contemporary Hollywood disaster films, however, where a protagonist’s proto-messianic preoccupation with the coming disaster and indifference to trivial worldly concerns is precisely what ennobles then, what is meant to make them sympathetic—it is here Leon’s fatal indifference and literary self-absorption that make him a humanist emblem of a more general “turning away” from the disasters raging everywhere around us. When the time comes for the “disaster to take care of everything” in Roter Himmel, the mood is that which W.H. Auden famously distilled in the final stanza of his “Musée des Beaux Arts”:

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.12

Fig. 17: Pieter Brueghel the Elder (presumed), “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” Musée des Beaux Arts, c. 1550s

Footnotes

This title of this piece is purloined from the English translation of Alexander Kluge’s extraordinary film Der Angriff der Gegenwart auf die übrige Zeit from 1985. Epigraph is from Marc Augé, The Future, London: Verso, 2014, p. 24. ↑

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Critique of the Judgement of Taste, translated by Richard Nice, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 67. ↑

www.arsenal-berlin.de/en/forum-forum-expanded/forum-expanded-program/installations/comrade-leader-comrade-leader-how-nice-to-see-you/. ↑

David Shields, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, New York: Vintage, 2010. ↑

Jussi Parikka, “Operational Images: Between Light and Data,” e-Flux, no. 133 (Feb 2023), www.e-flux.com/journal/133/515812/operational-images-between-light-and-data/. ↑

Paul Schrader, “Rethinking Transcendental Style,” in Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2018), pp. 1–35. ↑

See T. J. Clark, “Capitalism Without Images,” lecture at University of Chicago, November 30, 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MryiJVcsHkQ&ab_channel=uchicagoarts. ↑

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “James Benning’s Four Corners,” in Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons, (Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), pp. 113–18. ↑

Maurice Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster, translated by Ann Smock (Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995). ↑

For a superb analysis of the volcanic settings of PPP’s mid period see Andreas Petrossiants, “Under Etna’s Shadow: Pier Paolo Pasolini and the Volcano,” e-Flux no. 121 (October 2021), www.e-flux.com/journal/121/424221/under-etna-s-shadow-pier-paolo-pasolini-and-the-volcano/. ↑

W. H. Auden, “Musée des Beaux Arts,” in Selected Poems, expanded edition (London: Vintage, 2007). ↑

About the author

Published on 2023-03-14 13:40