A Beautiful Deed: Art as Action

John Ruskin, La Bible d’Amiens, trans. Marcel Proust (Paris: Société du Mercure de France, 1904). Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

1. The World of Tomorrow and the Work of Art

In her key work The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt “propose[s] to designate three fundamental human activities: labor, work, and action.”1 As these three activities are an integral part of bíos praktikós, the realm of life centered around three corresponding basic conditions (life, worldliness, and plurality), the original title of Arendt’s book, which is preserved in the German edition, derived from the Latin translation of this Greek term: Vita activa.2 Arendt distinguishes things of labor from things of work. A tart is a thing of labor. Amiens cathedral is a thing of work, “something immortal achieved by mortal hands”3—a result of doing by homo faber. The tart, connected to the needs and desires of the body, and the cathedral, built to be prayed in, are not things of the same category. The latter, just as all things of work, is made to last, and this durability is essential. As Arendt states:

“Work provides an ‘artificial’ world of things, distinctly different from all natural surroundings. Within its borders each individual life is housed, while this world itself is meant to outlast and transcend them all. The human condition of work is worldliness.”4

“Outlast and transcend.” Amongst all the kinds of things of work, the work of art is the most durable and worldliest. Amiens cathedral, whether she visited it or not, was there before Arendt, and it was there before John Ruskin or Marcel Proust, both of whom most certainly did visit it. It is still there. Things of work can outlive humans. Originating in the past, they continue into the future. They offer humans an experience of the world’s durability and a link to an ideal that endures even when the work itself is gone: “[…] in its sheer worldly existence, every thing also transcends the sphere of pure instrumentality once it is completed,” Arendt writes, continuing:

“The standard by which a thing’s excellence is judged is never mere usefulness, […] but its adequacy or inadequacy to the eidos or idea, the mental image, […] that proceed its coming into the world and survives its potential destruction.”5

Arendt pointed out a further significant aspect, namely that things of work possess a quality allowing them to “shine and to be seen, to sound and to be heard, to speak and to be read.”6

To Marcel Duchamp’s famous koan “Peut on faire des oeuvres qui ne soient pas d’art?”[Can one make works that are not ‘of art’?],7 she would have accordingly retorted that the question is tautologous. The work of art is primarily a thing of work; its “art” aspect comes into play via that thing’s own specific qualities. More so than other things, an art work must be “strictly without any utility.” It must be “unique” and impervious to being used up like the abovementioned tart. Finally, the work of art cannot have a reliable “exchange value.” If it is exchanged, its value is arbitrary.8 These are Arendt’s parameters for things of work of art and, as I understand it, the fewer of these qualities a thing possesses the less a work of art it would be for her. So, actually, yes, one can make works that are not “of art”; as a matter of fact, most are (not). But if works are durable, without utility, and lack consistent values of exchange, then they are most likely works of art. Into this category we might place a painted canvas just as correctly as a hewn stone or selected bottle rack. Arendt, of course, did not take into consideration performances, improvisations, etc., as these sets are not part of making the world or worldliness. They are activities of a different realm. Following this argumentation, I propose that performance and action art as we know them today are anchored in the field of plurality, in the political field.

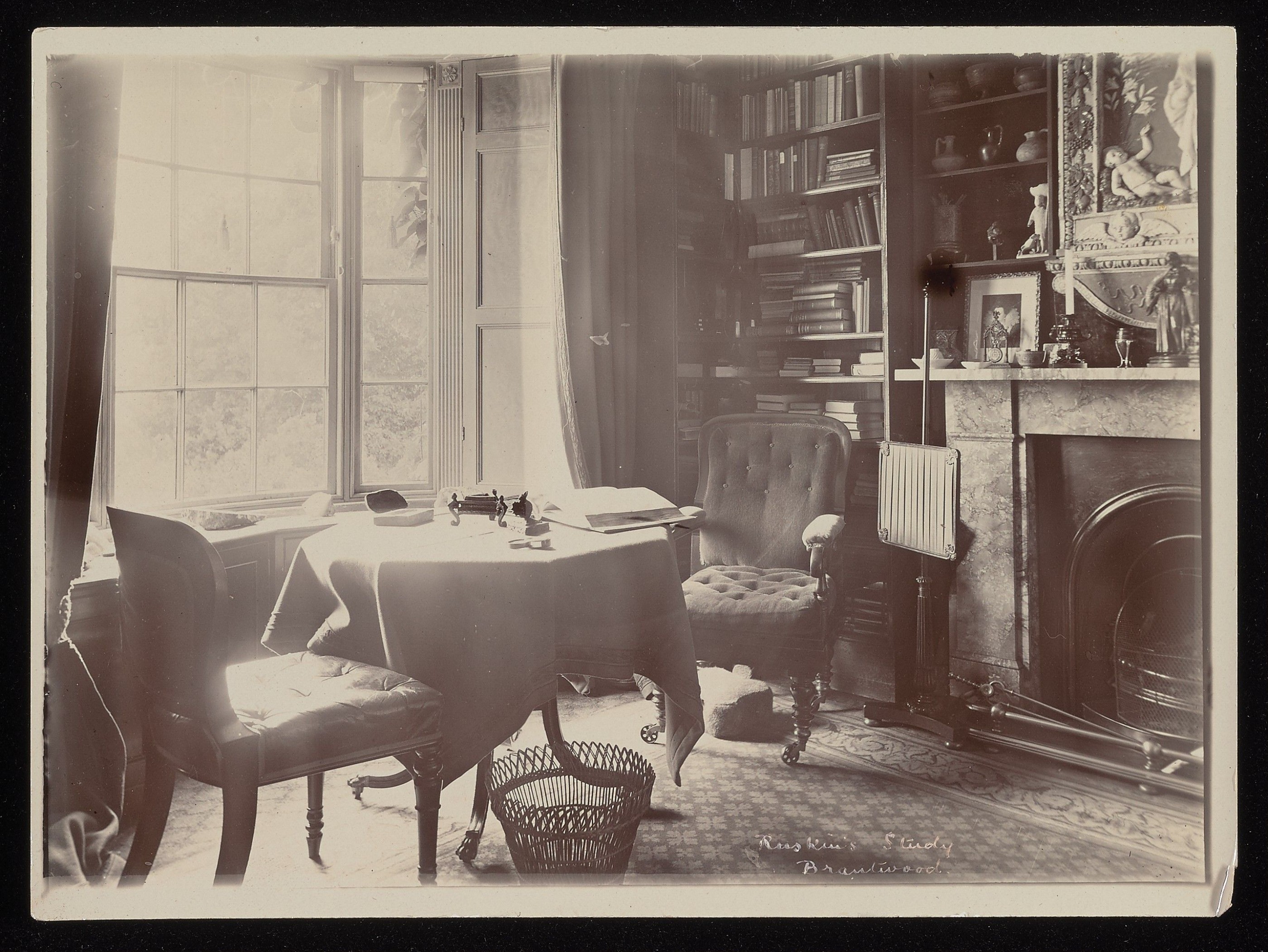

Photographic print of Ruskin’s study at Brantwood. Ruskiniana: pamphlets, biographical and critical, not dated. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

2. A Pilgrimage to the Past and the Body’s Role in It

When Marcel Proust visited Amiens cathedral, he made the trip as a pilgrimage, following the art historian John Ruskin’s journey to the same place.9 The world that day, as Proust travelled by automobile through the early autumn, came to him as though through “a kind of transparency,” at a remove that made it appear more conceptual and visual than real and tangible. His relationship to the world was defined by his separation from it, rendering the world as though it were “under glass.”10 Though still a child at the time of his first journeys, Ruskin, travelling in a “beautifully fitted coach,”11 also recalled experiencing the world as though it were “under glass.” For him as well, the relation of his gaze to the world was characterized by a separation, by a sort of transparent barrier: held in isolation from the sensual whole, Ruskin was imprinted by the world as though he were receiving it from a great distance. He kept these sensual imprints stored away, with each connected in his memory to a sense of himself, the observer, and with each by itself, separate. “[T]he infinitely multiple on the one hand, and the simultaneously unified on the other,”12 as Rosalind Krauss defines Ruskin’s “sensuality” in her famous critique, The Optical Unconscious, in which she indicts Ruskin for his failure to adequately account for the conclusions he drew from his observations. Krauss uses Ruskin’s method against Ruskin’s gaze, understanding his attempt to find an unalterable truth in vision as actually being a search for a persuasive framework for a canonical history of modern art. The two essential themes of Krauss’ text could be summarized as: “The optical and its limits. Watch John watching the sea.”13 And, indeed, her readers follow her as she observes Ruskin in the midst of his observations and follow her narration of his recollections, ones in which his perspective becomes intermingled with the things he was seeing. In Krauss’ analysis, Ruskin becomes the ridiculous advocate of autonomous art whose claim to offer objective truths found in the act of seeing crumbles in light of his own self-representation as an individual. For her, the result of Ruskin’s paradoxically writing as both an individual and a voice for that which can emerge via a unified, objective gaze is, in the end, a big hot mess. Ruskin’s work is “[p]rolix, endlessly digressive, a mass of description, theories that trail off into inconclusiveness, volume after volume, a flood of internal contradiction.”14 Be that as it may, it is Ruskin’s world “under glass” in its relation to the gaze of an author or artist that is of interest here. By observing his act of observation, the invisible line that, once crossed, allows observation to enter into processes of reification is revealed. These are processes through which the ephemeral, temporal moment of an individual’s observation becomes a durable thing of work.

When we observe things of work as manifestations of the reification of thought—when we “watch John watching the sea,” or, in Niklas Luhmann’s words, when we “re-enter” things of work through a “second-order observation”15—a different kind of approach is required. The mess of the past can only be brought into order through the observations of an historian, someone who can integrate both first and second-order observations: “Historical facts are timeless and discontinuous until woven together in stories,”16 as David Lowenthal, author of The Past Is a Foreign Country, contends. This argument would seem, for two reasons, to confirm Krauss’ suspicion that Ruskin was a bad historian, or, as I suggest, not a historian at all: his facts were not facts but, rather, impressions, and he in turn failed to weave these together into coherent stories.

“[T]he stories,” Arendt writes “[…] reveal an agent, but this agent is not an author or producer. Somebody began it and is its subject in the twofold sense of the word, namely, its actor and sufferer, but nobody is its author.” 17 Proust understood Ruskin’s legacy as resting precisely on the impossibility that the latter could be a “twofold subject,” suggesting that Ruskin’s importance is not as a conveyer of truths but as a sensual genius who attempted to control future perceptions of the works with which he dealt. Proust the writer reads Ruskin the writer differently than Krauss, who chooses instead to interpret him as a historian who is not one. However, Proust’s narration of Ruskin’s approach both to the cathedral and to his narrative is a “second-order observation.” He, too, is observing Ruskin observing as he makes his way to Amiens, albeit by re-enacting the latter’s physical journey: “[…] I was performing a lofty act of piety towards Ruskin. […] I thought I felt him directing my gesture.”18 Proust closely follows Ruskin’s suggestions of how to encounter the cathedral—physically, practically—though far less so his approach to understanding the thing of work itself, and he is willing to insert his physical self into the experience of the now observed observer. If it is a “fine day,” Ruskin recommends, as though expressly for Proust, one should approach the cathedral by the town’s Main Street and an adjacent hill. On a “gloomy day,” however, he recommends to “stop for a moment along the way so as to get into a good mood, and buy some tarts and sweets in one of the charming little pastry shops on the left.”19 All of this serves as a reminder that the observer needs a body to re-enact the past.

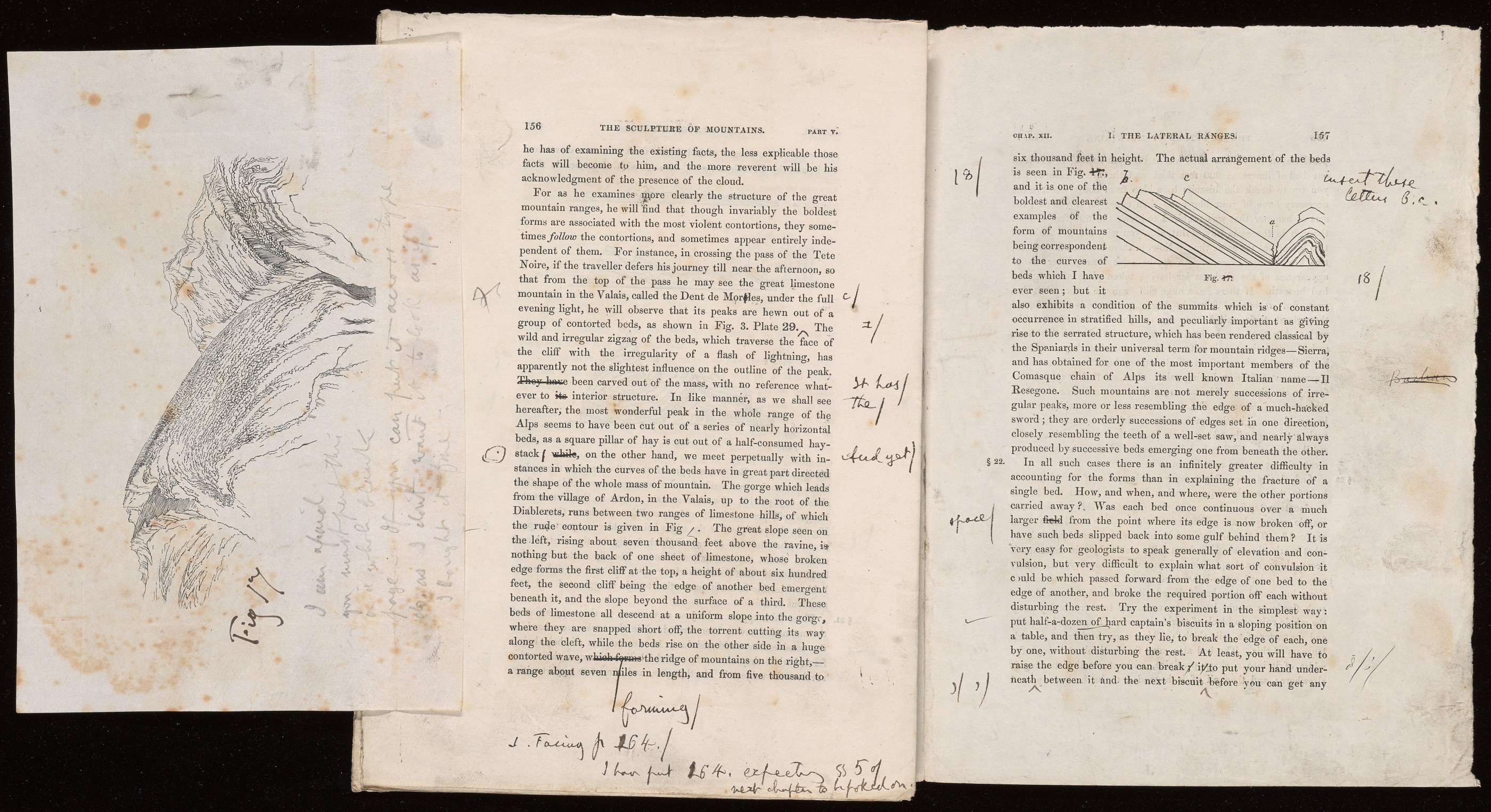

Modern Painters: Page proofs of Volume IV, Part V, “Of Mountain Beauty,” with manuscript corrections. In an orange half-morocco box case, not dated. John Ruskin Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

3. A Beautiful Deed: Art as Action

Theorist Judith Butler, in their Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, focuses on Arendt’s concept of appearance. They understand it as an integral part of the human condition of plurality, wherein the body consequently becomes an aesthetic means through which action occurs:

“Indeed, the very conception of human action as pervasively conditioned implies that when we ask the basic ethical and political question, how ought I to act, we implicitly reference the conditions of the world that make the act possible, or, as is increasingly the case under conditions of precarity, that undermine the conditions of acting.”20

Here, Butler makes an intentional shift: the “basic” question, as articulated by Kant, was, in fact, “What ought I to do?” and not “How ought I to act?” Butler changes the word “do,” which connotes the activities of labor and work and the basic conditions of life and worldliness, to the word “act,” which comes, of course, from “action,”

“the only activity that goes on directly between men without the intermediary of things or matter, [and] corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world.”21

Accepting this shift, one may then ask: What if the work of art is to be found neither exclusively in its “made” worldliness and in a durability reaching from the past into the future, nor purely in the transformative process that occurs between sensual body and the world, but, rather, in the realm of action and, thus, of plurality?

Such a shift from the work of art to the work of art as action can be illustrated by two historical examples, one from the avant-garde and another from the neo-avant-garde. “5x5=25” was the title of a now famous 1921 exhibition in Moscow, for which five artists, including Alexander Rodchenko, submitted five works each. Among Rodchenko’s contributions were three monochrome canvases that are today widely known as a single tryptic: Pure Red Color, Pure Blue Color, and Pure Yellow Color. The series consists merely of a successive presentation of the primary colors. The works were perceived at the time as radical heralds of the end of painting. Categorized in this way, the paintings were at first read as the initiation of something so radically new that nothing else, nothing newer, could follow. Yet, over time, observers became accustomed to the radical purity of paintings such as Pure Red Color, Pure Blue Color, and Pure Yellow Color, and could locate in them a beauty familiar from more “conventional” works of art. The “failure” of these works to retain their iconoclastic power was not due to the medium of painting being the wrong one per se for an attempt to leave behind their own status as “made” things and become “things of the world.” The degree to which the paintings require of their viewers an act of pure seeing, rather than a more wholistic sensual experience of them, meant that the paintings could not be transformed from a group of durable works of art into the embodiments of a process of action without end: “The reason why we are never able to foretell with certainty the outcome and end of any action is simply that action has no end.”22 These painted canvases—as observed objects—do not contain within themselves such a process of action: they “end” when the viewer averts their gaze from them. The crucial point in art as action, I would like to suggest, is that it makes possible the reification of a concept without binding the gaze to any objects produced, which would have the effect of rendering them necessarily as things of the past. No matter how iconoclastic a work may appear, and regardless of the medial form it takes, as a reification of thought, it quickly becomes a thing.

The monochrome paintings produced by the neo-avantgardist Yves Klein, on the other hand, are different in that they initiate a “deconstruction as second-order observation”:23 it is impossible to look at them without reflecting upon one’s own experience of one’s own gaze. The state of the monochrome paintings as works of art dissolves under the gaze and they enter a process leading to action in a different way than the classical work–observer sequence could allow. Or think of Barnett Newman, who argued that painting had the potential to be a means of escape: “[...] the elements of sublimity in the revolution we know as modern art, exist in its effort and energy to escape the pattern rather than in the realization of a new experience.”24 Maybe the things of works of art by Klein and Newman only appear to be paintings or, in other words, things of work. I would argue that they are actually simultaneously actions and reified actions. Not in the sense that in them the painting hand performs an action (that of applying paint) nor in the sense of their being relics of past actions, but, rather, in that the content of such paintings does not remain on the canvas but deposits its worldliness into the physicality of their appearance as observations being observed, reified, and then observed again as such.

As if to ensure that the shift of the work of art into the realm of action was accomplished with the utmost emphasis, in the late autumn of 1960 Yves Klein courageously put aside canvas and brush to jump from a rooftop in Fontenay-aux-Roses, Paris. Entitled Leap Into the Void, it was an utterly useless, beautiful deed. Judging by the expression on his face in the documentation of his action, the flying artist appeared to have felt a curious sense of “relief” in leaving worldly ground.

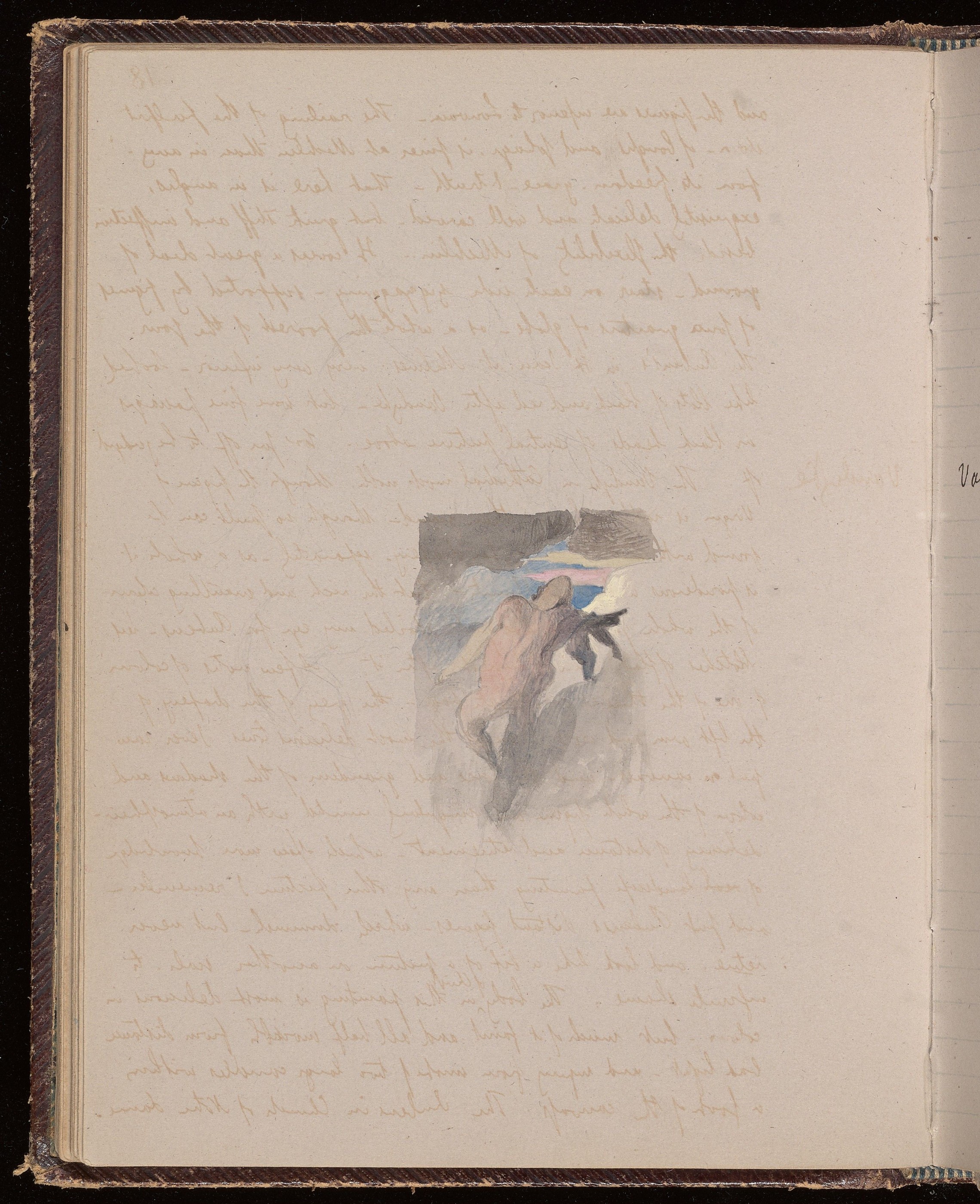

Manuscript notebook with watercolors, sketches, and drawings. Bound in purple full calf, May-September 1842. John Ruskin Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

***

Shortly before Arendt published The Human Condition, and almost exactly three years before Klein’s jump, another lift-off from the ground occurred. In late 1957, Sputnik 1 made its way into space and stayed there until the following January, when the craft was burned up during its re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. Like many others, Arendt watched news coverage of the lift-off and, engaging in her own act of second-order observation, was in awe at the apparent “relief” of the crowds of people who attended the launch.25 She saw them as registering that the heretofore utopian dream of being able to permanently leave the earth had suddenly become a future within reach. She was deeply concerned. In this desire to escape from earth, human beings were expressing their wish to leave a world that they themselves had built. She saw that this desire would mean the end not of humans themselves but of the work, their work, on which the possibility for acting and speaking in public lay, that is, the possibility to appear. Yves Klein’s beautiful deed, on the other hand, was a lift-off that did not enact an exit but, rather, an entrance. Leaving the worldliness of painting, as Klein did when he jumped, lead him into action. His jump was into the human condition of action, linked to what Arendt described as “the most elementary and authentic understanding of human freedom.”26 In the unexpected moment of a leap into action, it was a work of art that became an “activity […] without the intermediary of things or matter.”27

Edited and translated by Everett Forrest Mason.

Footnotes

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1958), 7. ↑

The translation of the German edition was done by Arendt herself and published with the title Vita activa oder vom tätigen Leben in 1967 by Piper, Munich. ↑

Arendt, The Human Condition, 168. ↑

Ibid., 7. ↑

Ibid., 173. ↑

Ibid., 168. ↑

Marcel Duchamp, In the Infinitive / The White Box (Cordier & Eckstrom Gallery: New York, 1966), n.p. ↑

Arendt, The Human Condition, 167. ↑

Marcel Proust translated John Ruskin’s The Bible of Amiens along with a preface and notes some years after Ruskin’s death in 1904. ↑

Marcel Proust, Pastiches and Mélanges by Marcel Proust, trans. R.A. Goodlake Lowen (Bell & Clews, 2018), 67. ↑

Rosalind Krauss, The Optical Unconscious (Cambridge, MA & London: MIT Press, 1993), 5. ↑

Ibid., 6. ↑

Ibid., 2. ↑

Ibid., 1f. ↑

Niklas Luhmann, “Deconstruction as Second-Order Observing,” New Literary History 24, no. 4 (1993): 763–82. ↑

David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985), 220. ↑

Arendt, The Human Condition, 184. ↑

Marcel Proust here “follows” the descriptions offered in John Ruskin’s publication of 1858 entitled The Two Paths. Proust, Pastiches and Mélanges by Marcel Proust, 78f. ↑

Ruskin, quoted in: Ibid., 77. ↑

Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press:, 2015), 23. ↑

Arendt, The Human Condition, 7. ↑

Ibid., 233. ↑

See Luhmann, “Deconstruction as Second-Order Observing,” 763–82. ↑

Barnett Newman, cited in Paul Crowther, “Barnett Newman and the Sublime,” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 7, no. 2 (1984): 54. ↑

Arendt, The Human Condition, 1. ↑

Ibid., 225. ↑

Ibid., 7. ↑

About the author

Published on 2023-08-03 12:00